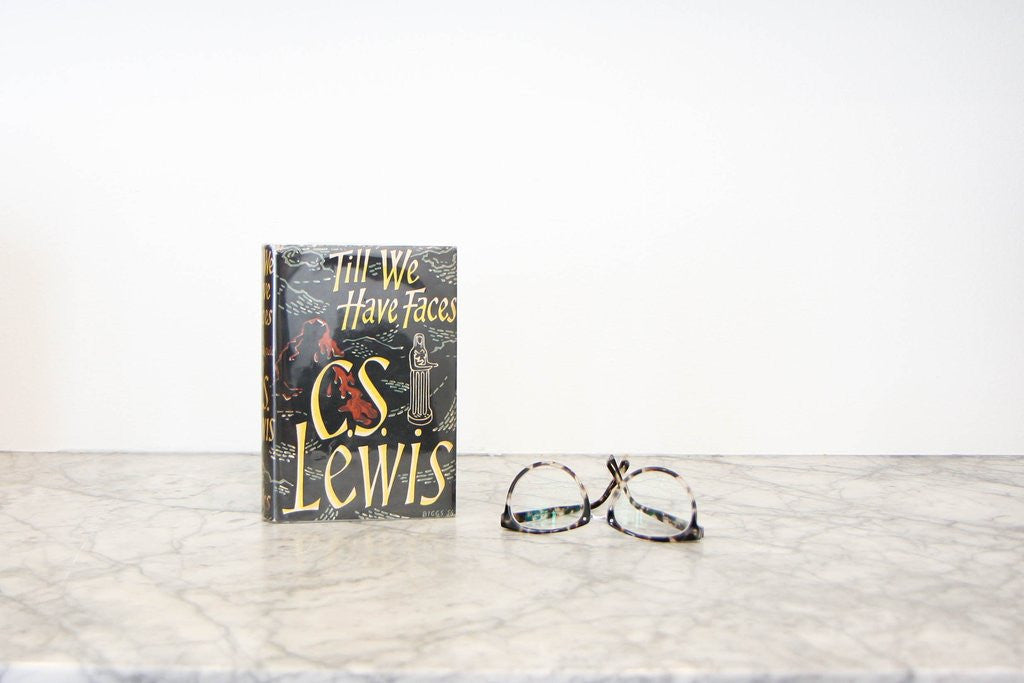

Last month, I faced what I believed to be an impossible task. We read my favorite book of all time for book club, and how could I do it justice? C.S. Lewis is a favorite author of mine, and Till We Have Faces is, bar none, the best book I've ever read. And yet, anything I say to explain it falls short. Even the word “favorite” does it a disservice. I have a favorite ice cream, a favorite color, but books—particularly this book—are so much more to me. How do explain what this book does for me, heart, soul, and mind? How do I explain that I have other favorites that I will turn to like familiar friends, but I avoid reading Till We Have Faces often? I'm not afraid that familiarity will breed contempt, but, perhaps, complacency. Maybe I'll begin reading with only my eyes and forget all that this book has given me.

C.S. Lewis was, and still is, a towering figure. A man of soaring intellect and a man of deep faith, he wrote in a way that challenges the mind. Non-fiction, literary criticism, memoir, children's literature, science fiction, myth—he wrote it all and he wrote it all well. It is possible to read his fiction simply for the story and still be satisfied, but I think you're missing the point. Lewis said that, “For me, reason is the natural organ of truth; but imagination is the organ of meaning.” I think that's what I love so much about him; everything he writes is imbued with purpose and meaning. Frankly, I think his non-fiction is brilliant, but I can't tell you much about it without a bit of quick research. His fiction, on the other hand, has taken root in me. It so deeply entwines my thoughts that I become almost inarticulate when I explain how he influences me.

Till We Have Faces retells the myth of Cupid and Psyche through the eyes of Psyche's oldest sister, Orual. It takes the tale we vaguely remember from high school English and turns it on its head as Orual makes her case. As the story opens, Orual has already convinced Psyche to betray her faith in Cupid, and Psyche is suffering the consequences. Having been the instrument of so much pain, Orual boldly declares that, “I will accuse the gods.” She is convinced that this tragedy is not caused by her jealous love, but by the duplicity of the gods. Her case is fascinating and flawed; Orual, however, is convinced that she bears no responsibility for her sister's plight.

This book can be read on so many levels. It is interesting simply as a twist on an older story. It is an exploration of love—between sisters, between friends, between teacher and pupil, between men and women. Till We Have Faces is also intended to point us towards faith. Lewis, along with his friend, J.R.R. Tolkien, believed that all myth serves to illustrate that great truth of Christianity. As I’ve often commented at book club, though, the conversation never goes quite as I expect. I saw all of these levels, and a few more, but I was surprised at what caught people’s attention. Some took the opportunity to study the mythology more deeply. One person commented on the fact that Orual was a truly empowered feminist model—I can see it, but I missed that completely as I concentrated on her guilt and her anger. Several people pointed out what I had missed on previous readings and barely paid attention to this time—Orual was not able to see herself as others saw her. She was so focused on her own largely negative feelings that she missed the love and respect that others felt for her. The title is difficult, too. Orual asks, “How can (the gods) meet us face to face till we have faces?” What does that mean? Years of loving this book, and it took someone from the club to articulate it cleanly. Orual hid her face behind a veil; obviously, no one could truly see her. However, she couldn’t see anyone else clearly, either. Her veil was always in the way. How could the gods speak plainly to her when she always hid herself from them? How could she see how others viewed her when her own view was always obscured?

Reading is a solitary activity. However, it is enriched by a great community. Others can help us sharpen our focus and define our thoughts. They can help us answer big questions. In the case of this book club, I had to answer, for myself and others, why do I read? And, why this book? I read for enjoyment, of course. I enjoy Orual and I enjoy judging her case. Occasionally, for growth. I watch Orual grow and I grow with her—in understanding and in heart. Also for knowledge. In this case, knowledge leads to growth. It's not just knowledge of the plot lines; more importantly, it's knowledge of motivation and truth. Finally, although rarely, for self-awareness. Truthfully, I don't read seeking self-awareness. In this case, I can't avoid it. I don't have a beloved baby sister married to an invisible god, living in an invisible palace, wearing invisible finery. I do, however, have lots of reasons why the consequences of my thoughts and actions are simply not my fault. I am intelligent enough (or vain enough) to rarely verbalize those thoughts—I don't want to look stupid. But, internally, I sure can wallow in a good case of finger-pointing. In the end, maybe that's what I love about this book. I enjoy it, but it makes me uncomfortable. Growth is uncomfortable. And maybe that's why I rarely re-read this book. I can name books that aren't my “favorite” that I've read a dozen times. In the last 20 years, I've read Till We Have Faces only three times. After reading this book, it worms its way into my thoughts and emotions for weeks—and it bubbles to the surface for years. At the end of her complaint, Orual questions of the reader, “Why must holy places be dark places?” In my case, as in Orual's, maybe it's because going through such dark places is the only way we can see and believe the light.

Tracy Bailey